Systems Analysis & Design

Contents

Visual Paradigm

Software required for this course: Visual Paradigm (Community Edition) You must register but it is a free trial version

Link to Visual Pardigm community edition (free): http://www.visual-paradigm.com/download/community.jsp

Visual Paradigm User's Guide: https://www.visual-paradigm.com/support/documents/vpuserguide.jsp

Xtra-vision express URL (Importante: revisar esto para la próxima clase)

Click https://xtra-vision.ie/how-it-works/ link to open resource.

UML

The UML (Unified Modeling Language) is an international industry standard graphical notation for describing software analysis and designs.

Para entender y practicar el UML nos vamos a basar en el ejemplo descrito en el libro «A STUDENT GUIDE TO OBJECT-ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT». The aim of this book is to describe what happens when a computer system is developed for a small business, in this case «the Wheels bike hire company». The approach used is object-orientation, which means that the whole development process is based round the object- a thing or concept that initially represents something in the real world and eventually ends up as a component of the system code.

Fundamental UML models

There are five fundamental UML models:

- Use case model

- Class model,

- Sequence model

- State model

- Activity diagrams

Use case model

The use case model consists of:

- A use case diagram,

- A set of use case descriptions,

- A set of actor descriptions, and

- A set of scenarios.

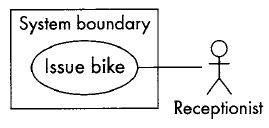

A use case diagram

The use case diagram models the problem domain graphically using four concepts:

- The use case,

- The actor,

- The relationship link, and

- The boundary.

UML symbols used to model these concepts:

- A use case: an ellipse labelled with the name of the use case. Conventionally we start each use case name with a verb to make the point that use cases represent processes. So we have 'Maintain customer list' rather than 'Customer list', 'Handle enquiries' rather than 'Enquiries'.

- An actor: a stick figure labelled with the name of the actor. We capitalize actor names so that they are easy to identify as such (e.g. Administrator, Receptionist). The stick figure icon is used even when the actor is non-human, e.g. another computer system or an organization.

- A use case relationship: a line linking an actor to a use case. The line shows us which actors are associated with which use cases. This relationship is also known as a communication association.

- The boundary: a line drawn round the use cases to separate them from the actors and to delineate the area of interest. Can be labelled to indicate the diagram domain. The boundary is often omitted.

The use case

What we do when identifying use cases is to divide up the system's functionality into chunks, into the main system activities. What dictates the split is what the user sees as the separate jobs or processes (the tasks he will do using the system).

Identifying use cases from the actors: There are several ways of approaching use case identification. One is to identify the actors, the users of the system, and for each one, to establish how they use the system, what they use it to achieve.

If we look at the interview in Chapter 2 we can see that Annie and Simon start off by talking about issuing bikes, one of the main jobs that make up Annie's working day. Issuing bikes therefore will be one of the use cases. Issuing bikes involves: finding a suitable bike, calculating the hire charge, collecting the money, issuing a receipt and recording details of the customer and the hire transaction.

The interview moves on to discuss dealing with the return of a bike. Annie sees this as a separate job from issuing the bike, it is separated in time and involves a different set of procedures- checking the date and the condition of the bike and returning the deposit.

Annie tells us in the interview that a list of bikes is already held on the computer, but they do not seem to be able to use it to help them in their work. The bike list needs to be stored so that it can be used to answer queries about what bikes Wheels have, whether they are available or on hire, what their deposit and hire charges are and so on. Maintaining this bike list is another use case.

Handling queries is seen by Annie as a separate job from issuing bikes. She often gets people coming into the shop or phoning just to check on the range of bikes available and get an idea of costs. This sometimes leads to a hire, but more often it does not. We can therefore identify Handle enquiries as a separate use case.

It also emerges from the interview that no record is kept of customer details or of what bikes they have hired on previous occasions. This sort of information would be useful for marketing purposes and to simplify dealing with requests for the same bike (see the Problem Definition (Figure 2.6), the Problems and Requirements List (Figure 2.7) and the Interview Summary (Figure 2.8)). Maintain customer list can therefore be identified as a use case.

Identifying use cases from scenarios: Another approach to identifying use cases is to start with the scenarios. We have already mentioned scenarios in Chapter 2 - a scenario describes a series of interactions between the user and the system in order to achieve a specified goal. A scenario describes a specific sequence of events, for example what happened when Annie successfully issued a bike to a customer.

Each use case represents a group of scenarios. Scenarios belonging to the same use case have a common goal- each scenario in the group describes a different sequence of events involved in achieving (or failing to achieve) the use case goal. A continuación, we describe scenarios belonging to the 'Issue bike' use case; in both cases Annie is trying to issue a bike to a customer.

Successful scenario for the use case Issue bike:

- Stephanie arrives at the shop at 9.ooam one Saturday and chooses a mountain bike

- Annie sees that its number is 468

- Annie enters this number into the system

- The system confirms that this is a woman~ mountain bike and displays the daily rate (s and the deposit (s

- Stephanie says she wants to hire the bike for a week

- Annie enters this and the system displays the total cost s + s = s

- Stephanie agrees this

- Annie enters Stephanie~ name, address and telephone number into the system

- Stephanie pays the s

- Annie records this on the system and the system prints out a receipt

- Stephanie agrees to bring the bike back by 9.ooam on the following Saturday.

Scenario for "Issue bike" where the use case goal is not achieved:

- Michael arrives at the shop at 12.oo on Friday

- He selects a man~ racer

- Annie see the number is 658

- She enters this number into the system

- The system confirms that it is a man's racer and displays the daily rate (€2) and the deposit (€55)

- Michael says this is too much and leaves the shop without hiring the bike.

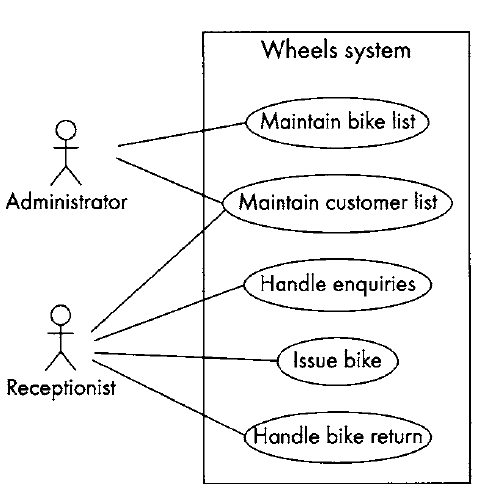

En la siguiente figura we shows a use case diagram of the Wheels case study. The functionality of the new system has been divided into five use cases: 'Maintain bike list', 'Maintain customer list', 'Handle enquiries', 'Issue bike' and 'Handle bike return'. Conceptually a use case diagram is similar to a top-level menu which lists the five main things that the system does. Each use case is linked by a line to an actor. The actor, represented by a stick figure, is the person (sometimes a computer system or an organization) who uses the system in the way specified in the use case or who benefits from the use case.

Use case descriptions

The use case description is a narrative document that describes, in general terms, the required functionality of the use case.

The class diagram

The class diagram is central to object-oriented analysis and design, it defines both the software architecture, i.e. the overall structure of the system, and the structure of every object in the system. We use it to model classes and the relationships between classes, and also to model higher-level structures comprising collections of classes grouped into packages. The class diagram appears through successive iterations at every stage in the development process. It is used first to model things in the application domain as part of requirements capture. Subsequently, with classes added which are part of the solution not the problem domain (e.g. interface classes), it is used to design a solution. Finally, with classes added to facilitate the implementation (e.g. buttons, windows, mouselisteners, etc.), it is used to design the program code.

Stages in building a class diagram

One way to approach the class diagram is by use case realization. In use case realization we look at each use case in turn and decide what classes we would need to provide the functionality modelled in the use case. The group of classes required by a use case is called a collaboration. When each use case has been analysed, the resulting collaborations are amalgamated into a unified class diagram. We will look at collaborations in Chapter 6, but for the moment we are going to use a different approach to developing the class diagram. We will develop a domain model, i.e. a class diagram that sets out to model all of the classes in the problem domain in one go, not use case by use case. Both approaches should eventually arrive at the same model.

Stages to build a class diagram (domain model):

- Identify the objects and derive classes

- Identify attributes

- Identify relationships between the classes

- Write a data dictionary to support the class diagram

- Identify class responsibilities using CRC cards

- Separate responsibilities into operations and attributes

- Write process specifications to describe the operations.

Identify the objects and derive classes

Class diagrams are a very useful way of modelling the structure of the objects in a system and the links between them. However, when we are trying to design a new software application, we don't know what the classes are in advance and we will often start by looking for objects before making decisions about what their class will be.

Objects come in different categories; being aware of the categories gives us an idea of the sorts of things to look for. Objects at the analysis stage will be things that have meaning in the application domain. They can be:

- People (such as customers, employees, students, librarians)

- Organizations (such as companies, universities, libraries)

- Physical things (such as books, bikes, products)

- Conceptual things (such as book loans and returns, customer orders, seating plans).

Various techniques can be used for object identification, none of them are foolproof, none can be guaranteed to produce a definitive list of objects and classes; they are just guidelines that might help. A good starting point is to look at the documentation about the system produced so far and to search for nouns in any description of the system requirements, preferably one that is complete and concise.

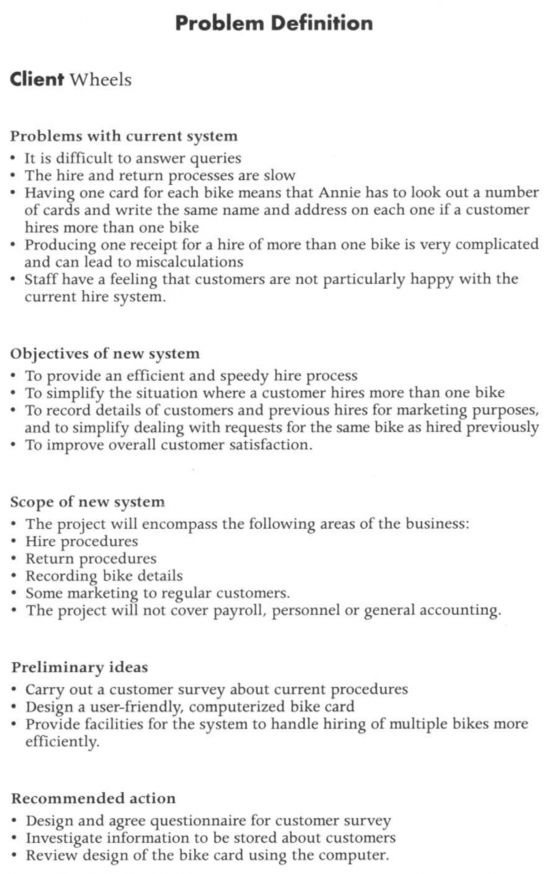

Object identification using noun analysis:

- First, find a complete but concise description of the system requirements. The Problem Definition in Figure Figure 1 (Chapter 2 del libro) is often a good place to look. Use case descriptions are also useful for this purpose, although for a complete description of the system you would have to look at all of the use case descriptions.

- Pick out all of the nouns and noun phrases and underline them. This usually provides a rather long list of possible (or candidate) objects, many of which are obviously unsuitable and some of which are unsuitable in more subtle ways.

- Reject unsuitable candidates by applying a list of rejection criteria.

For our object analysis we will use the list of requirements produced at the end of Chapter 2:

- R1: keep a complete list of all bikes and their details including bike number e typer sizer maker modelr daily charge rate, deposit; (this is already on the Wheels system)

- R2: keep a record of all customers and their past hire transactions;

- R3: work out automatically how much it will cost to hire a given bike for a given number of days

- R4: record the details of a hire transaction including the start date, estimated duration, customer and bike, in such a way that it is easy to find the relevant transaction details when a bike is returned

- R5: keep track of how many bikes a customer is hiring so that the customer gets one unified receipt not a separate one for each bike

- R6: cope with a customer who hires more than one bike, each for different amounts of time

- R7: work out automatically, on the return of a bike, how long it was hired for, how many days were originally paid for, how much extra is due

- R8: record the total amount due and how much has been paid

- R9: print a receipt for each customer

- R10: keep track of the state of each bike, e.g. whether it is in stock, hired out or being repaired

- R11: provide the means to record extra details about specialist bikes.

The candidate objects that result from this exercise are:

- list of bikes

- details of bikes" bike number, type, size, make, model, daily charge rate, deposit

- Wheels system

- record of customers

- past hire transactions

- bike

- number of days

- details of a hire transaction: start date, estimated duration

- customer

- receipt

- different amounts of time

- return of a bike

- total amount due

- state of each bike

- extra details about specialist bikes.

We now examine the list of candidate objects and reject those that are unsuitable. Objects should be rejected if they are:

- Attributes: Sometimes it is clear that a noun is an attribute of an object rather than an object itself. Bike number, type, size, make, model, daily charge rate and deposit are clearly attributes of a bike object rather than objects in their own right. Similarly, hire transaction sounds like a possible object, with start date and estimated duration as its attributes. Number of days also sounds like an attribute as do different amounts of time, total amount due and extra details about specialist bikes. Specialist bike, however, sounds like an object. If in doubt ask yourself whether the noun you are considering would be likely to have attributes of its own. Would it have behaviour?

- Redundant: Sometimes the same concept appears in the text in different guises. Here past hire transactions and hire transaction are probably the same thing. Different amounts of time, number of days and estimated duration are probably the same thing - all three refer to the length of a hire (in any case they are attributes, not objects).

- Too vague: If we don't know exactly what is meant by a term it is unlikely to make a good class. For this reason we reject return of a bike as an object. Return of bike is really an event and features in our use case model. Any data we might need to store about bike returns (e.g. date of return) can probably be bundled with the data about hires.

- Too tied up with physical inputs and outputs: This refers to something that exists in the real world but is a product of the system or data input to the system and not an object in its own right. For example, a bill exists in the real world, but is something the system outputs from data it already stores and as such would not be modelled as a class. Receipt qualifies for rejection under this heading. Receipt is an output; it is also redundant as we either store or can calculate the details we would print on it. List of bikes also requires some consideration. If we have an object to represent each bike, we can use these objects to produce a list. Bike, therefore, is a good candidate object, but we can drop the list at this stage. The same applies to record of customers and customer.

- Associations: In the class diagram in Figure 5.1 hires is modelled as an association between Customer and Bike. Whether hires is an object or an association raises some interesting issues and we will postpone that decision until later. The general rule in this situation is that if there is data associated with the relationship (and in this case there is), then we probably want to model it as an object.

- Outside the scope of the system: In this category would be anything we have decided to be beyond the system boundary. For example, according to the Problem Definition in Chapter 2 the system will not cover payroll, personnel or general accounting.

- Really an operation or event: This criterion is quite confusing and should be treated with care. If a candidate object seems to have no data associated with it, then it might be better modelled as an operation on another class. Quite often, however, operations and events are modelled as objects. For example, hiring a bike might be described as an event but as there is associated data, start date and number of days, we are more likely to want to model it as an object (see below).

- Represent the whole system: It is not normally a good idea to have an object that represents the whole system; we want to divide the system into separate objects. Wheels system should be rejected for this reason.

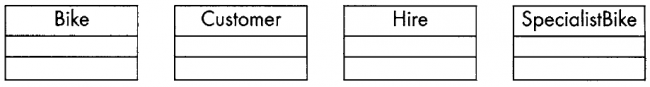

That leaves us with the candidate objects:

- bike

- customer

- hire transaction

- specialist bikes

We can use these objects to form the basis of our class diagram (remember that class names are always singular):

Sequence diagrams

CRC cards

Software developers find that the simplicity of CRC cards, their lack of detail, make them an ideal tool for exploring alternative ways of dividing responsibilities between classes. It~ easy to scrap one design and start again without agonizing about the amount of work that is being discarded. Another way of exploring alternatives is to use sequence diagrams, which are discussed later in this chapter. In practice, however, sequence diagrams show too much detail and are too slow to draw to be useful for this purpose. They are much more useful for documenting the detail of design decisions once these have been reached using CRCs.